Prompt Images

Before we dive in, I have to set the record straight. Unlike the rest of the Internet over the past 36 hours or so, this article is not actually about “covfefe.” Well, at least not entirely. But in case you’ve been living under a rock recently, or perhaps are browsing this page at some point in the distant future, I’ll set the stage. The rest of you, join me in a couple paragraphs.

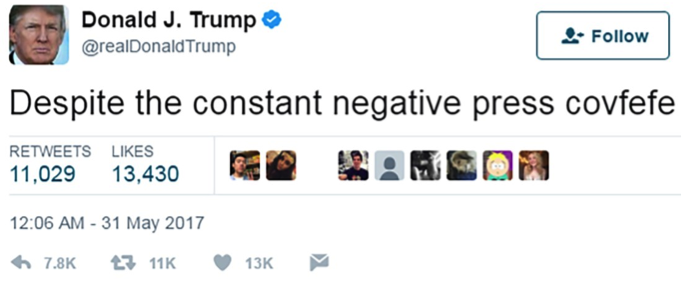

As some of you may know, at 12:06 A.M. Eastern Time on May 31, 2017, current President of the United States Donald Trump tweeted something to his millions of followers that quite literally made no sense.

Exhibit A.

Social media was instantly ablaze with curiosity. How did this happen? Speculation ran the gamut: a coded message to the Russians, a simple typo, evidence that cooler heads took POTUS’s phone away from him mid-tweet, signs of a stroke or seizure. For his part, Trump deleted the message the next morning and appeared to suggest there was a hidden meaning, asking “Who can figure out the true meaning of ‘covfefe?’”

But by that point the Internet had naturally already been doing lots of just that.

While amusing (to a degree), the hysterics are missing a larger, stranger point. Isn’t it weird that a bunch of people are debating the meaning of something that clearly has no meaning? There’s obviously humor involved. But that just sets the stage for another question: how could this be funny? A bunch of nonsense letters strung together shouldn’t be able to represent anything—that’s exactly the opposite of how our language works.

So what gives? Turns out you’re just using your hidden superpowers.

Psychologists used to think that babies learned how to talk1 in the same way that they learned how to ride a bike or tie their shoes. The recipe was trial and error, reinforced through responses from family members and others. The child who says “I runned in the park,” might get a gentle correction: “‘Ran.’ Say ‘I ran in the park.’” This confuses the child, who’s referred to things in the past before by adding -ed and not getting corrected. So you’ll hear them continue to say runned for a while, until they “learn to get it right.”

The same thing is going on with the family-favorite “pasketti” and “spaghetti.” The kid makes a mistake, is corrected, and eventually figures it out. And at first glance, this doesn’t seem like a bad explanation. After all, kids hear other people say a lot of words before they start talking, and when they do start talking they pick it up astonishingly quickly with few errors (relatively speaking). Over time those errors get ironed out and by the age of 5 or so, children can speak nearly as well as any adult. Usually.

Sometimes adults don’t speak well. Scientists are still unsure if there is an actual thought here.

So what’s going on when we read “covfefe?” We know it’s not a word. But, it could be! Maybe it’s a word we just haven’t seen yet, like when high schoolers study Shakespeare. Or maybe it’s a new word! After all, when I was a kid, there was no “selfie,” but we’ve since given it a meaning. “Brexit” is totally a thing, as are (sigh) “yolo” and “bae.” We make new words all the time.

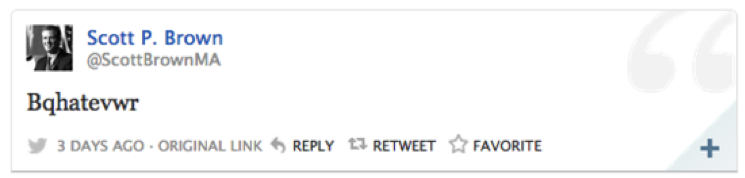

But take a look at another political, non-word tweet from 2013. This is definitely not a word.

Bqhatevwr, bro.

Here’s where the idea of “learning language is like riding a bike” begins to fall apart. No one ever taught you a list of letter combinations that aren’t words. So how do you know “bqhatevwr” is 100 percent not a word, but “covfefe” could be? And even weirder still, you know that “bqhatevwr” could never be a word. It won’t matter how many generations of slang go by, no one’s going to say their new fidget spinner (or whatever the latest fad thing is in the year 2050) is “bqhatewvr.”

Something more awesome is going on. Something a lot cooler than just learning how to ride a bike. We know “bqhatevwr” isn’t a word because we have a type of superpower. We know a lot more about English than we think.

As it turns out, English is nothing special—all languages are a type of superpower. Humans, as a species, have brains that are equipped at birth to learn language. Children are born ready to build a system to communicate with others, with no training required. Up until about 5 or 6 years old, their minds are busy processing the language around them and developing your average kid into a fully fledged language speaker.

Any child can learn any language. If the kid grows up around Mandarin, they’ll learn to speak Mandarin. They’ll speak Portuguese if they’re surrounded by Portuguese. Even children who have no hearing/speaking impairments will pick up American Sign Language from parents who use it. And if someone is lucky enough to grow up around two languages? Then they become completely bilingual—even if they hear only one language at home and another language at school.

There’s a deadline involved, though. The mental system responsible for learning language, called the language acquisition device (LAD) and theorized by the linguist Noam Chomsky, doesn’t keep processing information forever. At about 5 or 6 years old, it shuts down. Anyone who has tried to learn another language as a teenager or adult knows that you can spend years of study and never learn as quickly and easily as a native 5-year-old speaker. Their LAD has simply stopped and they can’t access the same mental systems.

But as a cognitive system, the LAD needs a starting point to work with. This starting point is a biologically built-in structure called universal grammar (UG) 2, again from Chomsky. Think of it as a set of possibilities that the LAD shapes into an actual language based on what the child hears in their environment. It’s sort of like a catered banquet where you’re allowed to select one salad, one drink, two appetizers, an entrée, and two desserts. You have choices for each dish, but you can’t ever order completely off the menu. (Seriously, try going to a gourmet restaurant and asking to customize/substitute something on the menu. The chef will probably come out and murder you on the spot.)

Here’s a helpful example: In Spanish, you can say, “Yo quiero Taco Bell.” You could also say just “Quiero Taco Bell.” They both mean “I want Taco Bell;” you don’t have to say “yo” = “I.” The subject is optional. Italian is the same way. But English and French? The subject is definitely not optional. In English, saying “want Taco Bell” is going to get interpreted as a question and not a statement about yourself. Same for “veux du Taco Bell.”

Going back to the menu analogy, languages have two choices for the “subject” dish: required and optional. However, you can’t order off the menu: there are no human languages that require you to say the subject twice.

Back to “covfefe” and “bqhatewvr.”

We know the second can’t be a word because the universal grammar has a menu of choices for what sounds are allowed to be mashed together in a word. The selections of dishes on that menu for English allow for the sounds that make up “covfefe” to happen together. The same rules also dictate that “bqhatewvr” isn’t an allowed group of sounds. You almost definitely wouldn’t be able to explain what those rules are—they’re not something you ever explicitly learned.4 But you know that “bqhatewvr” sounds wrong in a way that “covfefe” doesn’t.

So in all the kerfuffle (a real word) over “covfefe,” don’t forget the important lesson. You and your brain are a marvelous superhero duo, teaming up to perform the mightiest of feats: human language.

Yet of course with great power comes great responsibility. We should remember the duty to pick our words carefully, especially in this day and age where clarity of communication is critical. We need to realize that dialects, such as the vowel-lengthened Southern Drawl or the verb-dropping Black English, are literally meaningless when it comes to deciding if someone is speaking “real” English. Finally, with all the chatter about immigrants in America, we’d do well to think about the fact that adults struggling to speak a second language are doing one of the hardest things their brains could ever attempt.

And for God’s sake, if we’re going to tweet, we shouldn’t fall asleep at the keyboard.

1 “Talk,” “hear,” and “speak” are used here for clarity. All of the above applies to sign language as well, and a more nuanced phrasing would be “communicate.” Unfortunately, this doesn’t readily distinguish between the roles of sender and receiver, i.e. ‘speaker’ and ‘listener. See also footnote 3.

2 This is by no means a proven theory, and the concept of universal grammar may actually be falling out of favor. But in general, linguistics has moved away from the idea that language is something we have to individually learn from scratch and more toward the notion that it’s at least partially innate. What that innate structure looks like, and how it’s accessed, are the new battlegrounds of linguistics.

3 Contrary to popular belief, American Sign Language is a fully-fledged language in and of itself and not simply “translating” English words to hand patterns. Here is a great illustration, from “Internet Slang Meets American Sign Language” at Hopes and Fears, about developing a sign for the newer term “photobomb:”

“…if a person is photobombing a crowd of people, this would require a different sign as opposed to a person photobombing another individual.”

4 In case you’re interested, there are 14 of them.