Prompt Images

Like 99.9999 percent of America, I am a huge fan of Stranger Things. There’s so much to love about the show: the soundtrack, the childhood camaraderie, the opening credits, the poignant moments between Winona Ryder and her children, the reference to Farrah Fawcett hair spray, the return of Paul Reiser, the soundtrack, the soundtrack, oh, and, THE SOUNDTRACK. [1]

In case you wondered, yes, Farrah Fawcett hair spray was a real thing.

And of course there are the borderline campy fantasy/horror tropes that one would expect from a show titled Stranger Things: telekinetic powers, demonic human (or dog) like creatures called demogorgons (or demodogs), and an alternate reality called “The Upside Down.” If you haven’t yet watched the show here is a description of The Upside Down from the Stranger Things wiki:

The Upside Down is an alternate dimension existing in parallel to the human world. It contains the same locations and infrastructure as the human world, but it is much darker, colder and obscured by an omnipresent fog. The Upside Down is devoid of human life, instead being overgrown with ropy, root-like tendrils and biological membranes covering practically every surface. At least one recognizable animal, a humanoid predator, was native to this dimension, while ash-like spores floated in the air.

Looks a lot like the bathroom in my freshman dorm—amiright?

Here’s the thing, of all the absurdities in the show, The Upside Down may be the least crazy. Modern physics, it turns out, is rife with theories that propose alternate dimensions that may exist “in parallel to the human world.”

Let’s take a brief tour through some of the leading candidates, shall we?

Extra Dimensions

In the fifth episode of the first season of Stranger Things, the boys seek advice from their oracle—their science teacher Mr. Clarke. They want to know if it’s possible for other “dimensions” to exist.

Mr. Clarke: Picture an acrobat standing on a tightrope. Thats our dimension. And our dimension has rules. You can move forwards or backwards. But, what if, right next or our acrobat there is a flea. And the flea can also travel back and forth, just like our acrobat, right? The flea can also travel this way, along the side of the rope. He can even go underneath the rope.

Mike, Dustin, and Lucas: Upside down.

Mr. Clarke: Exactly.

So the idea here is that to a person a tightrope may as well be 1-dimensional. There is some thickness to the rope—it has a circumference. But the person can’t really move around that dimension of the rope in any practical sense. But a flea is so small that it can crawl around the circumference of the rope in addition to moving forwards and backwards. In some sense there’s “an extra dimension” available to the flea that isn’t available to the tightrope walked.

That flea can go forwards and backwards like Star Girl here, but the flea can also go “around” the rope.

This analogy just so happens to come straight from the pages of various popular science books on string theory, which is a physics theory that posits there are extra dimensions to our universe that only tiny particles (the fleas of physics) can travel through. Except in string theory, the extra dimensions aren’t just really small versions of one of our usual three dimensions—they are microscopically small extra dimensions, and there are six of them, in fact.

With this analogy in mind, maybe The Upside Down could exist as a separate “world” in these other dimensions, which we, being too large to travel through the tiny extra dimensions, would never encounter. Basically, imagine Horton Hears a Who, but instead of tiny Whos on a flower, the Whos live in microscopic extra dimensions that are too small for an elephant to fit into.

Here’s the problem: string theory is still a rather speculative theory with no empirical evidence whatsoever and so should be taken with not just a grain, but an entire planet of salt.

Credit: XKCD

In other words: we may need to look elsewhere for The Upside Down.

The Multiverse

The idea that our universe might be one of many has been around for a long time, and the fodder of many science fiction novels. But the idea gained new momentum (pun intended) when physicists studying the aforementioned string theory discovered that the “equations” [2] of string theory allow for not just our particular universe, but a crap ton of other possible universes. And by crap ton I mean 10500. That is a gigantic number. Suck it Avogadro.

Now rather than stop and say, whoa this is a pretty crazy idea that has literally no empirical backing, maybe we should keep looking for some other new theory that could be tested with technology that might be available within the next 20,000 years, many physicists simply decided that physicists of the past had been a little too hasty in assuming there was just one universe.

For believers in the multiverse, there are as many as 10500 different universes that all exist somewhere. With those kind of odds, just about any universe is possible. Some of these universes would look nothing like ours: consider a cold dark universe where stars never formed at all. Others might be nearly identical except for some obscure distinction: like a world where Trump is president but ALF is still airing new episodes. Surely, by sheer probability, at least one of these other universes looks like The Upside Down, replete with “ropy, root-like tendrils and biological membranes covering practically every surface.”

On the other hand, the multiverse is a rather speculative idea that comes to us via string theory, which as I mentioned above is also rather speculative. Again, we may need to look elsewhere for the Upside Down.

There is one possibility though, that while still speculative in part, actually does make some contact with the physical theories we already know and love.

The Upside Down, meet the Hidden Sector.

The Hidden Sector

To understand what the Hidden Sector is, we need to understand how physicists currently model all of, well, everything.

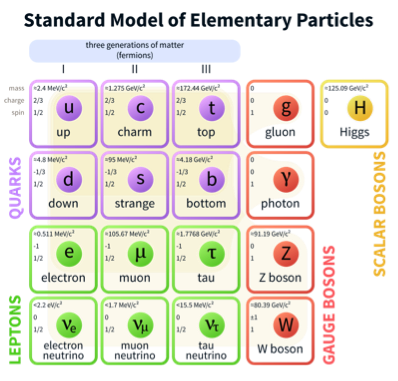

According to modern physics there is a set of fundamental (or elementary) particles that have mass and make up all the “stuff” in the universe. In addition to these elementary particles, there are four “fundamental” forces: the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force, electromagnetism, and gravity. That’s it. Every other force you can think of is ultimately due to one of these forces. [3]

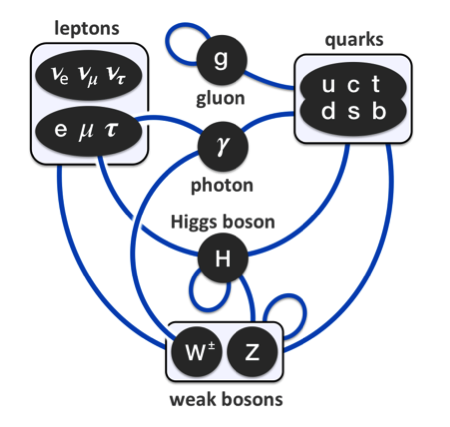

Here’s the physicists equivalent of the periodic table, which lists all the elementary particles:

Now notice the right column. These “particles”—referred to as gauge bosons— are actually associated with each of the four fundamental forces: the electromagnetic force is “carried” by photons, the strong force is carried by gluons, the weak force is carried by the W and Z bosons. Gravity is also presumably carried by gravitons, which aren’t shown in this table because no one has ever observed them—but most physicists believe in them anyways.

This diagram represents a process where two electrons (e-) come in from the bottom, exchange a photon (Ɣ) which acts to transfer energy/momentum between the electrons, and afterwards go flying off in different directions towards the top. This is literally one of the most fundamental processes happening all the time in the universe.

Each of the fundamental forces (and their corresponding carrier particles) may be thought of as a different “sector” of physics: There’s a strong sector, a weak sector, an electromagnetic sector, and a gravity sector. In each different sector, particles exchange different gauge bosons (in a similar process to that shown for the electron above), which result in the different kinds of forces.

Oh, and there’s also the Higgs, on the far right. You remember the Higgs—the particle that physicists discovered in the gigantic contraption known as the LHC a few years back? Yeah, the Higgs is one of these “elementary” particles that make up everything, though its precise role is complicated and beyond our purposes here.

Don’t worry about the details. Just know that according to this model, everything you know and love is the result of a complicated dance among different elementary matter particles and elementary force-carrying particles. They are responsible for building quarks protons and neutrons, and then building those into atoms, and then connecting atoms into molecules, and connecting molecules into humans (but also other biological creatures, rocks, etc.), and connecting humans into human pyramids.

The thing is, not all particles feel all the forces, and this is the key to understanding the hidden sector. For example, electrons feel the electromagnetic force from photons, and the weak force from the W and Z bosons, but NOT the strong force that is carried by gluons.

It turns out that elementary particles are like high school kids: cliquish. Electrons (part of the lepton family) do not interact with gluons, and so don’t feel the strong force.

And some particles, like neutrinos, only interact through gravity and the weak force. As the name implies, the weak force is really, really weak. How weak? Well, and I don’t mean to alarm you, but there are currently 65 billion neutrinos passing through every square centimeter of your body right now. The sun spits out an absurd number of neutrinos along with all that light (in the form of photons). But it’s OK, they don’t interact with the atoms in your body. Because the weak force is SO weak, neutrinos only interact with other particles on very, very rare occasions. (And they don’t weigh enough for gravity to matter much).

For all intents and purposes you are a ghost to those neutrinos (and vice versa).

Is this starting to sound familiar? Will?

There’s another class of as-yet discovered particles, which may not interact via any of the known fundamental forces except gravity: dark matter particles. You’ve probably heard of dark matter. That would be the 25 percent of the universe that we know must exist (based on how much gravity we observe in the universe), but for the life of us, we just can’t seem to find it.

Physicists talk about such particles as existing in a hidden sector.

And some physicists believe that there may be other kinds of particles that don’t interact via most of the usual forces and therefore, in some sense, remain hidden. Recently, in lieu of the failure to discover much new and exotic physics beyond the Higgs at the LHC, some physicists are dreaming up schemes to detect particles that might live in the hidden sector.

The Upside Down

With hidden sector physics we suddenly have something that sounds a lot like The Upside Down: a world made of other kinds of particles that would mostly just pass through the “stuff” in our world like it wasn’t even there. Not by traveling through other dimensions—these particles still move through the same three spatial dimensions (and one time dimension) that we do. It’s just that they don’t interact with the particles that make up the world as we know it (and vice versa).

And unlike some of the more speculative ideas mentioned above, we might be able to detect these hidden sector particles in the near future.

But, there are still a few problems with The Upside Down as the Hidden Sector.

First, even if we discovered hidden sector particles, we don’t know that there are enough different kinds to form interesting structures, like hidden atoms, or hidden molecules and/or hidden Reddit subthreads. As I said, we are currently bathed in a shower of neutrinos that are more or less hidden from us, but they don’t do anything interesting—they don’t really interact with one another.

Second, thanks to Einstein, all particles experience gravity [4]. Meaning hidden matter and non-hidden matter would feel each other’s gravitational pull. So it’s unlikely you could build a whole hidden world on top of our own, since we’d presumably detect all that extra gravitational force as extra pounds on the scale.

Third, even if there was an Upside Down in the hidden sector, it seems unlikely we could ever build a bridge to it, as is done in Stranger Things. For instance, there’s no way we know of to easily interact with all those ghostly neutrinos currently streaming through us and our entire planet.

In other words, if the hidden sector provides our best hope for an Upside Down existing somewhere, it’s unlikely that such an Upside Down would be a parallel version of our world with the same planet and buildings overrun with ropy vines. And there would likely never be a way to travel between our two worlds.

And yet, the hidden sector still leaves open the possibility that there is an entire world of exotic particles that exists “beside” our own. A dark and cold place devoid of all light (because the particles don’t experience the electromagnetic force, which is responsible for light).

A world without life or anything else save, perhaps, floating bits of dark detritus. [5]

Even without the demogorgons, it sounds like a pretty terrifying place to me.

Footnotes:

[1] Please feel free to listen to this epic opening theme on repeat as you read this piece.

[2] Actually, nobody knows what the “equations” for string theory are, which is why many people are skeptical of its preeminence as the leading theory of everything. It’s currently more of a hodgepodge of interesting theoretical “observations.”

[3] Actually, almost every force you can think of that isn’t due to gravity is due to electromagnetism. Every contact force, be it a push, a grab, or a hook and a jab—is ultimately due to the electromagnetic forces between the two contacting objects. Turn off electromagnetism and nothing could ever “touch.” Bonus, if you’ve ever told some special guy or gal you felt some electricity in that kiss—that would be a scientifically accurate statement.

[4] Well, Newton taught us all matter gravitates and Einstein taught us (via that infamous equation E = mc2) that energy and matter are in some sense interchangeable. So if something has energy—and everything that “exists” has some energy—it experiences gravitational forces, even if very weakly.

[5] PLEASE NOTE THAT THE AUTHOR OF THIS PIECE IS A WRITER FOR AN ONLINE MAGAZINE AND NOT A LICENSED PHYSICIST. ALL SPECULATION ABOUT ALTERNATIVE PHYSICS IS HIS OWN OPINION AND MAY NOT REFLECT THE OPINIONS OF THE PROMPT(™) OR ACTUAL PHYSICISTS.